Have you ever walked through a bustling city and felt a shiver down your spine, a sense of unease that seemed to emanate from the crowded streets? Perhaps you’ve wondered why certain areas seem to be plagued by crime while others remain relatively peaceful. This is the very question that captivated criminologist Robert E. Park, sparking a groundbreaking theory known as Concentric Zones Criminology. This theory helps us understand the environmental factors that contribute to crime, especially in urban areas, and it continues to be relevant today, providing insights into the complexities of crime and social inequality.

Image: www.researchgate.net

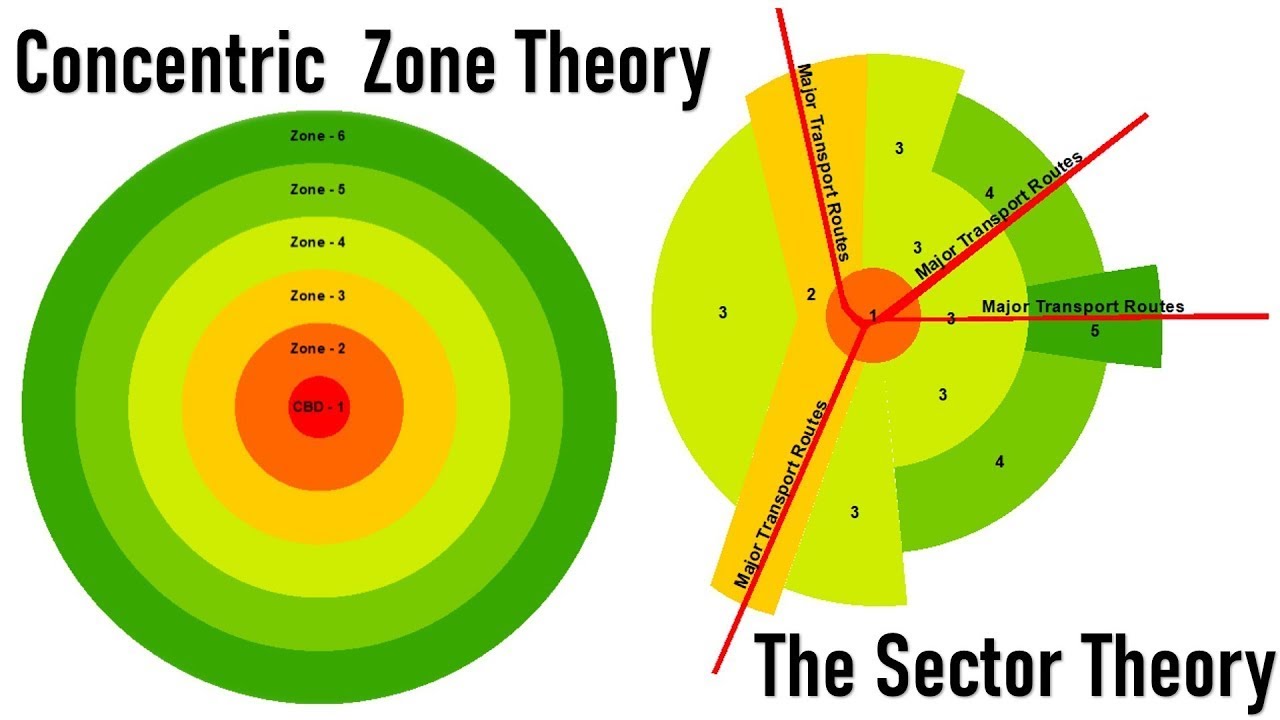

Concentric Zones Criminology, also known as the “Chicago School” of criminology, emerged in the early 20th century when Chicago was grappling with rapid urbanization, high immigration rates, and a surge in crime. Park and other sociologists observed that crime wasn’t randomly dispersed throughout the city. Instead, it clustered in specific areas, often following a distinctive pattern. This realization led them to develop the concentric zone model, which depicts the city as a series of concentric circles, each representing a distinct zone with its unique characteristics and social dynamics.

Unraveling the Zones: A City Divided

The concentric zone model, initially proposed by Ernest Burgess in 1925, envisions the city as a series of rings expanding outward from the central business district. The model, while simplified, captures the complex interplay of social forces that influence crime. Let’s delve into each zone to understand how it contributes to the overall crime patterns:

Zone 1: The Central Business District (CBD)

This bustling hub is characterized by skyscrapers, commerce, and a high concentration of people during the day. While crime exists within the CBD, it tends to be more focused on property offenses like shoplifting, vandalism, or white-collar crime. The transient nature of the population and the concentration of valuable goods make this zone a target for opportunistic offenders.

Zone 2: The Transition Zone

This is the heart of the concentric zones theory, considered the “zone of transition” where crime rates are highest. It’s often characterized by physical deterioration, poverty, a mix of industrial and residential areas, and high population density. Here, the pre-existing social structures have been disrupted. Families are often transient, and job opportunities are limited, leading to high unemployment and social disorganization. The lack of social cohesion, combined with the presence of poverty and inadequate infrastructure, creates a fertile ground for criminal activities.

Image: www.youtube.com

Zone 3: The Working-Class Zone

Moving outward, we reach Zone 3, populated by working-class families who often live in modest homes with some economic stability. Higher levels of social cohesion and the presence of local institutions can help mitigate crime rates in this zone. However, the presence of poverty and the influence of the transition zone can still contribute to crime, albeit at lower rates than in Zone 2.

Zone 4: The Residential Zone

This zone typically consists of single-family homes and more affluent families with higher levels of social stability. While crime rates are generally lower here, the residents might experience a fear of crime due to the proximity of Zone 3.

Zone 5: The Commuter Zone

This outermost ring comprises suburbs and rural areas where residents often have higher socioeconomic status and more established communities. Crime rates are typically lower in this zone, but suburban crime has become a growing concern in recent decades.

Understanding Social Disorganization

The central concept behind Concentric Zones Criminology, and perhaps its most impactful contribution to criminological thought, is the idea of “social disorganization.” This refers to the breakdown of social structures and controls within a community, leading to a decline in collective efficacy and an increased risk of criminal activity. In the transition zone, specifically, the absence of stable institutions, limited access to resources, and rapid social change create an environment where crime thrives. This social disorganization weakens social bonds, reduces community participation, and diminishes the ability of residents to collectively control crime.

The Legacy of the Concentric Zones Model

While the Concentric Zones model has been criticized for its simplistic representation of cities and for failing to account for the role of individual factors in crime, its impact on criminological thought is undeniable. It challenged the prevailing view that crime was primarily caused by individual pathology and emphasized the role of social structures and environments, laying the foundation for future theories in environmental criminology. The model underscores the vital relationship between poverty, social disorganization, and crime, highlighting the importance of addressing social inequality and fostering community development to prevent crime.

Modern Implications of Concentric Zones

Today, Concentric Zones Criminology continues to be relevant, helping us understand crime patterns in urban areas that have grown more complex due to globalization, technological advancements, and shifting social demographics. While the original model might need some adjustments to account for the changing urban landscape, the core principles remain instrumental in informing crime prevention strategies and urban planning.

Rethinking Community Development

The concentric zone model urges us to rethink community development and crime prevention initiatives. Investing in economically disadvantaged communities, promoting community organizing, and strengthening local institutions are essential steps towards building safer and more resilient urban environments. These interventions can help mitigate social disorganization, foster collective efficacy, and create opportunities for residents to thrive.

Addressing Systemic Issues

Furthermore, the model highlights the need to address systemic issues that contribute to social inequalities, such as poverty, lack of affordable housing, and limited access to education and employment. By tackling these issues at their roots, we can create a more just and equitable society that reduces crime and promotes social well-being for all.

Engaging in Effective Community Policing

The concentric zone model also advocates for a more proactive and community-oriented approach to policing. Instead of relying solely on reactive measures like arrests and surveillance, law enforcement agencies should engage with communities, build trust, and work collaboratively to address the root causes of crime. This involves promoting dialogue, fostering partnerships, and empowering communities to take ownership of their safety and wellbeing.

Utilizing Data and Technology

Data collection and analysis are essential for understanding crime trends and identifying potential hotspots. By leveraging technology and data-driven insights, we can target resources, implement strategic interventions, and enhance our understanding of how social factors contribute to crime. This allows us to develop more effective crime prevention programs and ensure that resources are allocated where they are most needed.

Concentric Zones Criminology

Moving Forward

Concentric Zones Criminology is not just a theory but a call to action. It challenges us to recognize the complex interplay of social factors that contribute to crime and reminds us that addressing crime requires a multifaceted approach. By understanding the social and environmental dynamics that contribute to crime, we can prioritize policies and interventions that promote social justice, economic equality, and community empowerment. These are the foundations for building safer, more inclusive, and thriving urban spaces.

The future of our cities lies in our collective efforts to address the root causes of crime, strengthen communities, and create opportunities for all. As we continue to navigate the challenges of urbanization and social inequality, the lessons learned from Concentric Zones Criminology remain as relevant as ever, guiding us towards a more equitable and just future.